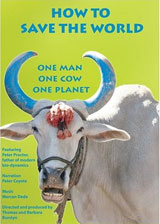

Biodynamic Farming

How to Save the World: One Man, One Cow,

One Planet.

A revolution in food production called biodynamic farming is the subject of the film ‘How to Save the World: One Man, One Cow, One Planet’.

Find this film and watch it. Watch it more than once. It is narrated by Peter Coyote which is reason enough but if your movie watching consists of one film a year, put Indiana Jones on hold until the DVD release and get this film. It is available through Earth Cinema Circle.

At first glance the task of saving the world appears to have fallen on an unlikely candidate. Peter Proctor is 80 years old but has single handedly spearheaded his farming movement in India. It has literally altered that vast nation’s agricultural landscape. Proctor is rather a biodynamic phenomenon in his own right and finds it difficult to find people half his age able to keep up with him. He has traveled all over the world teaching farmers how to create better food by creating better soil.

This revolution is over 100 years in the making. The true father of biodynamic farming, Rudolph Steiner (also the founder of the Waldorf school) was born in 1861. It is Steiner’s principles that Proctor has dusted off and applied in the Indian subcontinent.

Over twenty years ago India’s agricultural community employed what is now almost

comically referred to as a “green revolution”

in farming. This consisted of the liberal use

of chemical fertilizers and pesticides for the

purpose of increasing crop yields. It was an

unmitigated disaster. The effect on the soil

was essentially to kill it. Unable to produce

even enough food to feed their families,

farmers were forced into a cycle of depend-

ence on more and more powerful and expensive chemical additives while going deeper in debt. Meanwhile their crop yields were dwindling.

Proctor’s approach is to take what is immediately available; cow dung, water and composting materials such as leaves and biodegradable garbage and build long compost heaps to create rich soil for starving fields. The application of enriched material to the soil and the watering techniques create what one farmer calls a soil texture ‘like butter’. Proctor is a latter day Johnny Appleseed; he takes his solution to one farm at a time.

What allows us to call this a revolution is the impact on farming practises and the social effects of farming on a ‘human’ scale. The film charges us with another responsibility: we need to examine where our own food comes from and how much autonomy we have sacrificed at the altar of convenience. We seem not to have a problem with buying food products rather than food. The choice to be made is to whether or not to have giant agribusinesses decide what we eat and live with chronic disease or grow and eat our own food and be healthy. Peter Proctor has helped thousands of farmers not by railing against the problem but by living the solution.

|